10 things we've learned about A/B testing for startups

Contents

Every A/B test has four components:

- A goal

- A change

- A control group

- A test group

You’re testing a change (2) on your test group (4) to see if it has a statistically significant impact on the goal (1) compared to the control group (3).

But those are just the basics. In this week’s issue, we explore the secrets of running truly successful A/B tests (and some pitfalls to avoid).

This week’s theme is: Becoming an A/B testing ninja

This post was first published in our Substack newsletter, Product for Engineers. It's all about helping engineers and founders build better products by learning product skills. We send it (roughly) every two weeks. Subscribe here.

1. You need to embrace failure 📉

It shouldn’t surprise you when your A/B tests fail. This is true across the industry:

At Bing, only about 10% to 20% of experiments generate positive results, but they improved revenue per search by 10-25% a year.

Booking.com runs an estimated 25,000 tests per year. Only 10% of them generate positive results.

Using their “Universe” system, Coinbase ran 44 experiments in 8 months. 35 “resolved to control” – i.e. they showed no improvement.

Let’s Do This, a Y Combinator startup with $80M in funding, ran 10 or more A/B tests each week. 80% failed.

Thomas Owers, who ran growth at Let’s Do This, states engineers who run a lot of experiments "need to get comfortable knowing their code will be deleted."

He emphasizes two key points:

- An experiment isn't a failure if it doesn't produce the results you expected.

- An experiment is only a failure when the team doesn't learn anything from it.

Read about Thomas’ experience in How to start a growth team (as an engineer) on the PostHog blog.

2. Good A/B tests have 5 traits ✅

A specific, measurable goal An ambiguous goal leads to an unclear A/B testing process. It isn’t clear what A/B test to run to “increase sales.” “Increase demo bookings from the sales page” is actionable.

A clear hypothesis about why your change will achieve your goal A good hypothesis explains why you’re making the change, and what you expect to happen. Without one, how will you know if your test was successful?

Test as small of a change as reasonably possible Change too much and it’s unclear which (if any) change made a difference, and why. That said, a change is too small if it’s unlikely to impact user behavior, so choose carefully.

A sufficiently large sample size You need a large enough sample size for your test and control groups for them to be statistically significant. We calculate this automatically in PostHog, btw.

A long enough test duration Depends on your sample size and confidence level, but a good rule of thumb is a minimum of one week and a maximum of one month.

Read more about these traits in A software engineer's guide to A/B testing.

3. Use the “right place, right time” rule 💡

Right place, right time is a simple maxim for running successful tests.

Right place = Group your changes in as few places as possible, use feature flags to control who sees your changes, test only those involved in the test see the changes, and don’t capture metrics from unaffected users.

Right time = Use feature flags to control when your changes show, run your test to reach significance, and avoid the peeking problem.

- Create a proposal system 🏦 As we noted earlier, good tests need a clear hypothesis. A simple way to achieve this is to create a consistent process for them.

Monzo, the British online bank, asks four simple questions before running any test:

What problem are you trying to solve?

Why should we solve it?

How should we solve it? (optional)

What if this problem didn’t exist? (optional)

Answering these questions helps Monzo create consistent hypotheses containing a proposed solution to a problem, and the expected outcome. It also allows anyone to propose a test, including staff who don’t typically run experiments.

📖 Further reading:

- How YC's biggest startups run A/B tests (with examples) – Ian Vanagas

- How we experiment at Monzo – Monzo blog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Read by 100,000+ founders and builders

We'll share your email with Substack

5. Understanding significance 📊

There are two moments when you should analyze your goal, secondary, and counter metrics:

At launch, to make sure the test is working as expected.

At the recommended run time, to check for significance and make a decision.

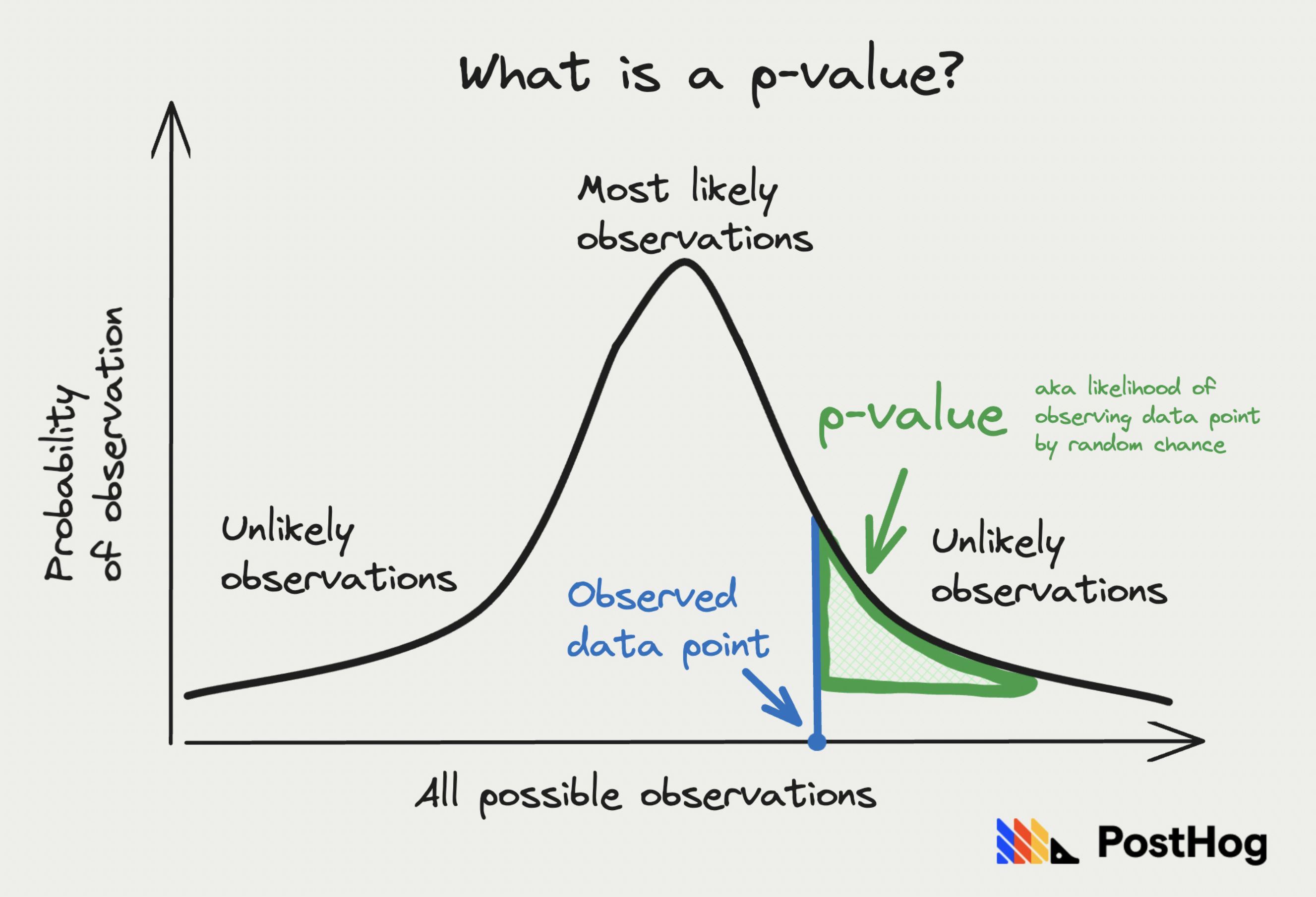

Statistical significance is generally found by calculating how difficult it would be to get the same (or more extreme) result by random chance if you didn’t make your change (aka the null hypothesis is true). This is known as a p-value. It enables you to set a significance level below which you can be confident your change is making an impact (aka reject your null hypothesis).

For example, a p-value of 0.05 means that if the null hypothesis is true, there is a 5% chance of observing the data or more extreme results purely due to random chance, and you can be 95% confident in your change.

Remember: lack of statistical significance does not mean your test is a failure. Other reasons for “failure” include not gathering enough data, too small (or large) a change, or aggregate results hiding significance in individual properties.

📖 Further reading:

- 8 annoying A/B testing mistakes engineers should know – Lior Neu-ner

*Note for statisticians: please don’t hurt me for simplifying this definition. If you’re really interested, here is a long Wikipedia article for you to read.

Enjoying this post? We send new ones every two weeks… and they’re free. Subscribe here.

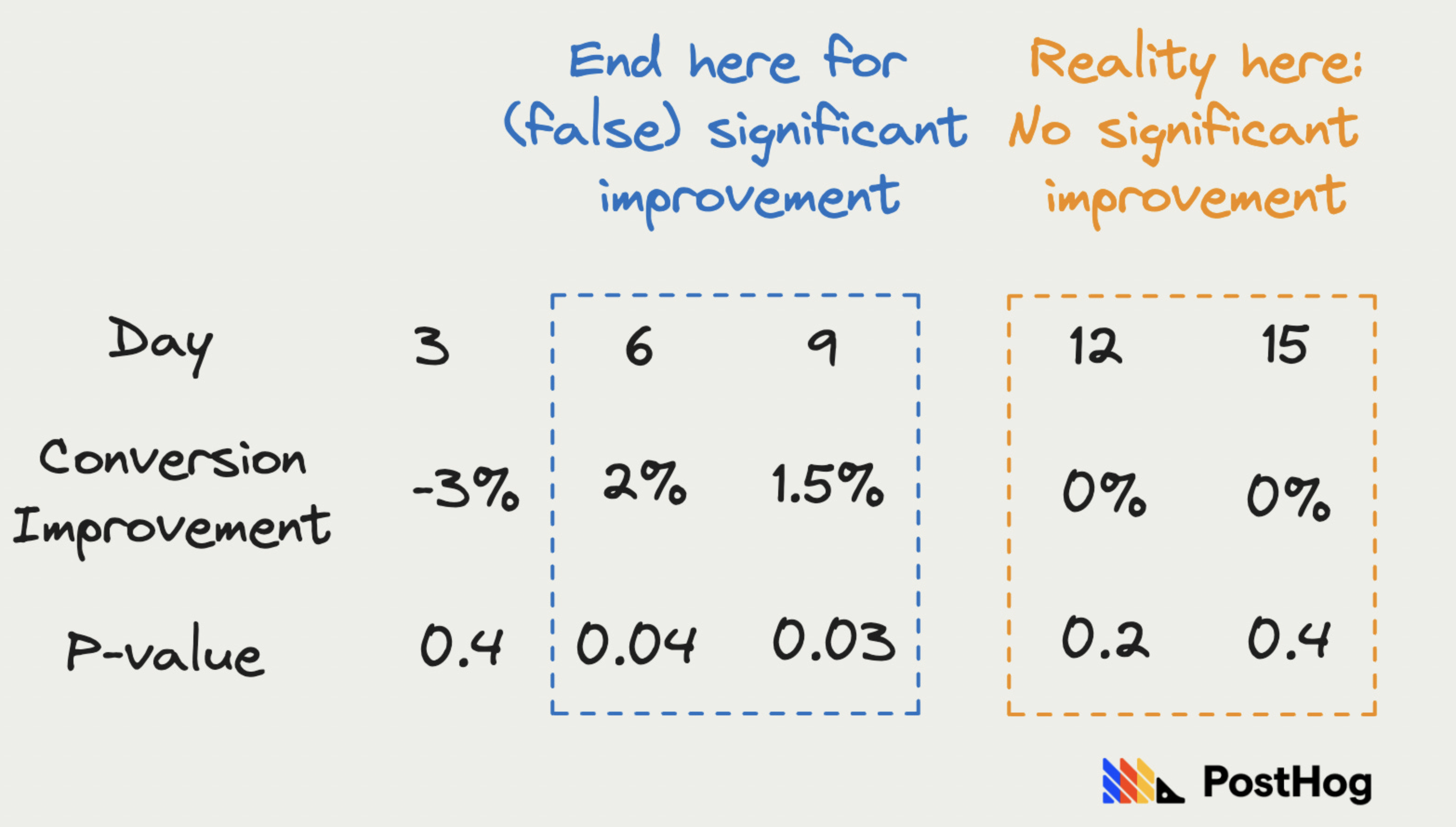

6. Beware false positives ⏳

It’s tempting to end A/B tests when you first get results. This is the “peeking problem” – where you make decisions based on early, but insignificant, data. Instead, you should run A/B tests to significance.

But, as Airbnb found out, peeking too early isn’t the only way to get false positives. They found a pattern of hitting significance, and then converging back to insignificant, neutral results in their experiments.

To fix this, they calculated a dynamic p-value curve using past experiments, which started at 0 and then curved up towards 0.05 on day 30. This helped them determine whether an early result was worth investigating.

PostHog A/B tests have a built-in running time calculator, which uses the minimum acceptable improvement and baseline event count to recommend a running time. You can find the full calculation for this in our docs, or try it out in-app.

7. You need a culture of experimentation 🧑🔬

A/B tests won’t magically happen. They must be part of your company’s culture. This happens by embracing these three values:

Data over debate. Data trumps opinions, even for executives. You need buy-in from all levels of the organization.

Experiment with everything. Say “I don’t know” and find out. Jeff Bezos once said, “Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per year, per month, per week, per day.”

Let everyone experiment. Good ideas can come from everywhere. ~75% of Booking.com’s 1,800 tech and product team members actively use the company’s experimentation platform.

8. Learn when NOT to use a test ❌

A culture of experimentation is great, but A/B tests aren’t the solution to every problem. You should avoid them when you have:

Insufficient traffic or time constraints… because you can’t hit statistical significance, which you need to make a good decision. This is especially relevant to early-stage products will small user bases.

High implementation or costs… because time and resources are scarce. Be careful about technical debt tests create, and make sure testing this feature is worth prioritizing.

Ethical considerations… because your users are real people and they are relying on your product. Running a test on a bug might verify your solution works, but some users will suffer needlessly.

Learn more in A software engineer's guide to A/B testing.

9. There are many different types of test 📝

Other types of tests exist beyond the standard A/B test, which compares two variants and their impact on a goal metric, such as:

Multivariate or A/B/n tests, which compare multiple (n > 2) changes and their impact on the same goal.

Holdout tests, where you leave a small percentage (~10%) of users on the old variant after you choose a winner to test the long-term impact on the goal.

A/A tests, where you compare the same change to see if the impact on the goal is not statistically significant. This is to test your A/B test service, functionality, and implementation work as expected.

Multi-page funnel tests, where you test changes to multiple pages in a flow (e.g. onboarding) to see what converts best.

10. Try targeting “actors” rather than users 🎯

Targeting your A/B test can go beyond just users. GitHub and GitLab instead use the concept of “actors”, which can include organizations, teams, pages, projects, and more.

Targeting individual users might cause unintended consequences and create inaccurate results. For example, a change in the Uber app for drivers likely affects riders' experience too.

Using actors ensures the experience (and results) for your A/B test are consistent and enables you to measure the impact of changes on the actor group as a whole, rather than individual users.

Read more about targeting in When and how to run group-targeted A/B tests.

Good reads 🤔

PostHog's recommended reading for startup teams – Joe Martin: Great books on leadership, design, venture capital, operations, and sales (pretty much anything to do with startups), as recommended by the PostHog book club!

How a startup loses its spark – John Qian: An interesting read diagnosing the many ways startups can become less enjoyable, and how to avoid them. The easiest one? Hire less. It’s one we believe in.

Stop Making People Make Up Their Mind – Stay SaaSy: A great read on the dangers of a “strong opinion” culture in a startup, and how to foster a culture of thoughtfulness instead. “Being right for the wrong reasons (or by chance) is just as worthless as being wrong.”

Beware of Price Cliffs – Good Better Best: A quick and useful lesson on how mental barriers can impact user behavior.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Read by 100,000+ founders and builders

We'll share your email with Substack

Words by Ian Vanagas, who is A/B testing whether pineapple belongs on pizza.

PostHog is an all-in-one developer platform for building successful products. We provide product analytics, web analytics, session replay, error tracking, feature flags, experiments, surveys, LLM analytics, data warehouse, CDP, and an AI product assistant to help debug your code, ship features faster, and keep all your usage and customer data in one stack.