How we choose technologies

Contents

Over the past 12 months, we have:

Expanded our usage of Temporal to power warehouse syncs.

Moved destinations and transformations away from Node virtual machines to our home-built HogVM in our own language, Hog.

Migrated more of our highest volume services from Python to Rust.

Evaluated Warpstream and Pulsar as alternatives to Kafka.

Adopted C++ over Python to speed up SQL parsing.

We did all this while shipping multiple new products, such as web analytics, mobile session replay, and our data warehouse, and dozens of new features for existing ones.

Ultimately, technology is just a tool to help us build something people want. We always want to choose the right ones, but lengthy procurement processes would slowly kill us. Shipping fast isn’t optional.

Our solution is trust and feedback over process and letting product teams own the process from beginning to end.

We can't tell you what technologies to use, or the perfect way to pick them, but this is how our company of ~60, remote and async people does it.

1. We prioritize hair-on-fire problems

Adopting new technologies is hard and expensive, so "nice to have" is not enough. Hair-on-fire problems typically mean one of three things:

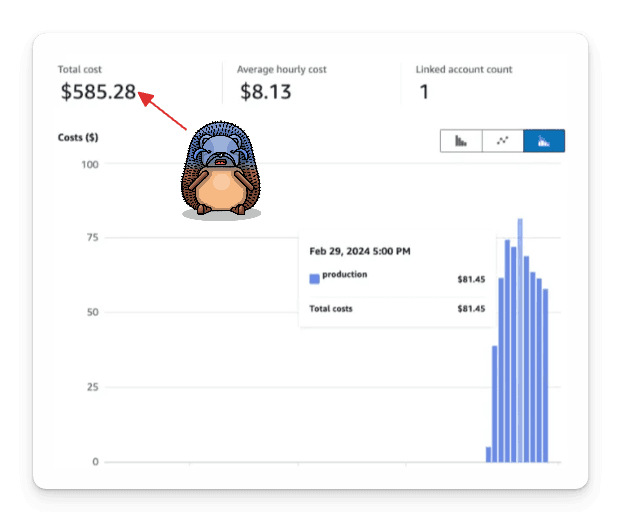

Excessive costs. Our infrastructure team does a quarterly review of AWS costs, evaluates where spend is going, and identifies areas to improve it. Costs rising above standard benchmarks is a trigger to look for solutions.

Scaling challenges. When we reach scaling limits for our current infrastructure, and adding "more boxes" won't fix the issue, it's time to look for another solution.

Customer needs. When customers demand a new feature, like reliable and resumable data exports, we need to consider whether we build or buy.

We find potential solutions in one of two ways:

What are other people using to solve the problem? Technologies are by definition tools or services other people have used to solve problems. One reason we chose ClickHouse, for example, was that Cloudflare used it.

How have YOU solved this problem in the past? It’s easier to solve problems you’ve encountered before. We lean on our team’s experience to evaluate options.

Researching options and evaluation happens simultaneously because our team knows some options can be written off immediately.

When we were looking for scalable replacements for Postgres in our early days, for example, we knew we needed it to be open source and self-hostable. This immediately eliminated options like Snowflake, Redshift, or BigQuery.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Read by 100,000+ founders and builders

We'll share your email with Substack

2. We evaluate as close to reality as possible

Bias for action is one of core values. This means:

Individual small teams have the autonomy to choose and test technologies.

We don't have an elaborate planning or procurement process.

Instead of filling out paperwork and budget requests, our teams evaluate technologies as close to the real world as possible. They test in production (safely), mimic the real world, and build proof of concepts to test solutions.

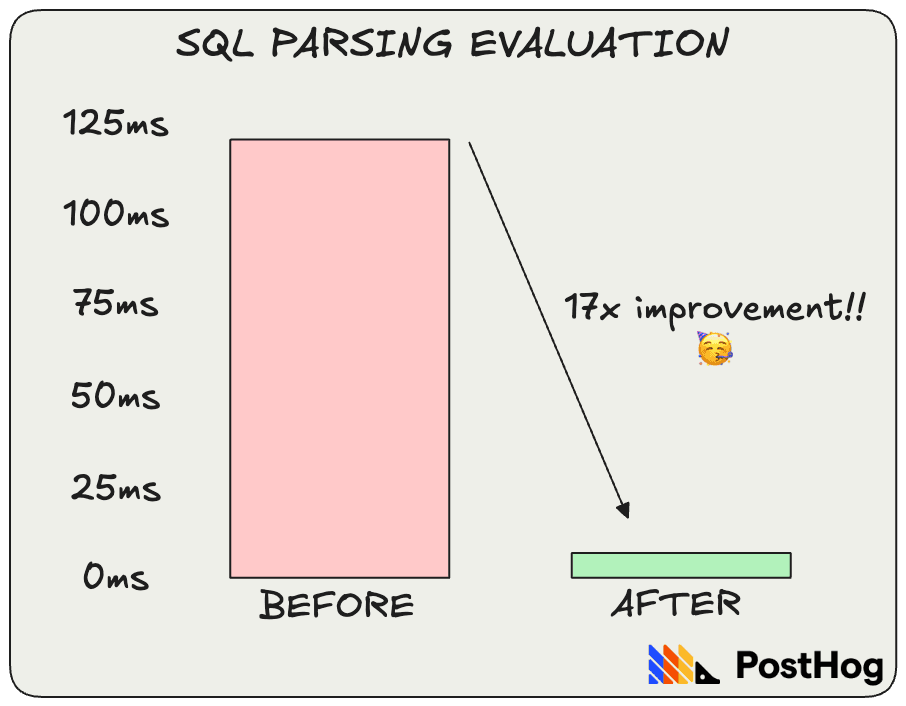

When Michael Matloka was looking for a fix to our slow SQL parsing, he evaluated technologies that could help, built a proof of concept in C++, and tested it with real slow queries. When he saw a clear improvement, roughly a 17x improvement on average (from 120ms to 7ms), he was confident in adopting C++ as the solution.

Another example is how we evaluated Warpstream. This evaluation was triggered by the high cost of Kafka, so the Infrastructure team chose to mirror traffic from our capture service to get an accurate projection.

Testing this way meant they could also evaluate Warpstream’s deployment process, provisioning, performance, and scalability at the same time, which saved time.

Testing technologies is often a non-trivial part of teams' development process. It is common to see tests or proofs of concept as a quarterly team goal. For example, building out a Warpstream proof of concept was a Q3 goal for the Pipeline team.

3. We consider technical AND business factors

Every problem has its own set of evaluation criteria, but there are some recurring themes:

Performance – We ingest billions of events per day and this will only grow. We need technology that can keep up and scale to 100x where we are today.

Cost – Being the cheapest option is an important pricing principle for us. This means we always look for ways to reduce costs, such as using S3 for replay storage instead of ClickHouse, which helped us make replays drastically cheaper.

Reliability – Companies rely on us to handle business-critical data. We need to maintain a high uptime and availability. Technologies we choose need to prove they are reliable and handle failures gracefully.

Support – Is this a shiny new thing or a battle-tested one? Is it open source with an active community? We need to know we can get help when we need it.

Flexibility – We plan to ship many products beyond what we have today, so we need technologies that are interoperable and adaptable to new use cases.

You'll notice that some of these are business factors and others are technical.

This is possible because product engineers can move faster by engaging with and understanding the broader business context, rather than relying on a product or procurement team to evaluate business factors separately.

4. We make decisions asynchronously

Although individuals are empowered to test and evaluate new technologies, decisions affecting multiple teams are made through a request for comments (RFC).

RFC's help us get buy-in, gather feedback on a decision, and stay transparent. Writing them also forces teams to clearly articulate their thoughts in a structured way.

An RFC outlines the "why" behind a technology decision and helps facilitate input. The specific parts of an RFC vary, but broadly include the following parts:

What is the problem you are trying to solve?

What are the options you considered?

Based on your evaluation, which one do you recommend?

This isn't just a box to tick, it’s a core part of helping us choose the right technologies and how we work asynchronously.

Our RFC for adopting Temporal at PostHog had 2,594 words, roughly 1/4 of the company as reviewers, 46 comments, and quite a bit of debate before finally being adopted. It's now happily in use for batch exports and warehouse syncs.

Whatever happens, the final decision usually rests on the team implementing and maintaining the technology. Even if an agreement isn't reached, if they feel confident it is the right solution, they have leeway to go ahead with adoption.

When do we say NO to technologies?

A well-researched and argued RFC normally results in a “yes”, but not always. Typical reasons for rejecting proposals include:

Lack of maturity. If we choose to adopt a technology and not build it ourselves, we need to be confident it is stable, reliable, and has the features we need.

Poor fit for other teams and projects. Because we have multiple products, we need technologies that work for multiple use cases. Input from other teams may prove a technology isn't the right fit, or seriously obstructs them.

Additional more important criteria surface. We rely on our teams experience to guide our evaluations. An RFC might miss important criteria someone has firsthand experience with that causes us to reconsider.

The evaluation goes against our expectations significantly. Research can show us what to expect, but it isn't perfect. This is why evaluating as close as possible to the real world is critical.

We chose not to adopt Amazon's Elastic File System (EFS) for the last reason.

The problem we had was that rebalances in our session replay service required pods to re-process historic data. This slowed throughput dramatically, which triggered more rebalancing, and created a negative cycle that caused multiple incidents.

By providing a persistent file system all pods could access, EFS eliminated the need to re-process data during rebalances. New pods could pick up where the last one left off, reading from the shared disk.

In our test of EFS with real data, rebalances had little effect on throughput and smaller warm-up costs. It seemed to be the solution, until the cost graphs caught up. We initially estimated $300/month, but this was based on an average throughput, not total.

The actual cost? $600/day! 😬

The team quickly concluded that, while this was an important problem, the cost was too high. Later, when testing Warpstream, we found a simpler solution: changing how we commit offsets to Kafka.

Rather than pushing commit messages (which could trigger rebalances if timed wrong), we declaratively told Kafka which offsets to commit. This made rebalances a non-issue. Now, when a pod needs to restart, other partitions continue processing normally instead of getting caught in a restart loop.

5. We continuously evaluate for the long-term

Finally, choosing a technology does not mean we’re done. Technologies have ongoing costs in terms of maintenance, support, recruitment, speed, and more. Why shouldn't your evaluation be ongoing also?

Because technologies have such a big impact in the long run, we often spend significant time doing planning related to our most important features, such as pipeline, data storage, and product roadmap. These plans include:

Problems or opportunities

Required and nice to have features

Potential solutions

Goals for the planning phase

Next steps

We even evaluate our most cherished technologies to ensure they are the right long-term choice. We've long been advocates of ClickHouse, but we still consider and test other technologies, such as ByConity and Apache Iceberg.

We do this because we want to build a technology stack that supports our long-term strategy:

Provide every tool needed to build successful products. This requires separation of compute and storage (this is tightly coupled in ClickHouse), flexibility in query optimization, and interoperability with future technologies.

Be the source of truth for customer and product data. We want to build towards handling exabytes of data stored and petabytes of data queried per day. This means managing different schemas, improving offline storage, support for formats like Iceberg and Parquet, and more.

Figuring out what we need in the future helps us build towards it now. We can set ourselves up to successfully adopt new technologies when the time comes, and deliver the best possible product to users over the long term.

Words by Ian Vanagas, technology appreciator.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Read by 100,000+ founders and builders

We'll share your email with Substack

PostHog is an all-in-one developer platform for building successful products. We provide product analytics, web analytics, session replay, error tracking, feature flags, experiments, surveys, LLM analytics, data warehouse, CDP, and an AI product assistant to help debug your code, ship features faster, and keep all your usage and customer data in one stack.