What the AI Wizard taught us about LLM code generation at scale

Contents

You know what’s boring?

Writing integrations.

It’s a task you’ll do once, but you always need to do it right, which means carefully reading docs. Since you're working with an unfamiliar library, there are always caveats you need to think about.

All of this sucks. So we built the PostHog AI Wizard: a command line tool that tailors a correct integration of our product for you.

This tool can understand your business goals, where churn happens, and the conditions for your success, all as expressed in your code.

And it can do this with just one command.

Try it out with your Next.js projects. We’re adding more frameworks and languages as you read this.

I spent a lot of 2025 anxious that none of this would work. The world of LLMs is strange: there’s not always an objectively correct way to do things. And it's so easy for the robot to run off and do something unexpected.

But with enough stubbornness, we cracked this: we can generate correct, predictable, automated PostHog integrations so you can get on with the work you really care about. And we can do it for thousands of customers every month.

You can use LLMs to generate correct and predictable code, too. Here’s everything we learned.

The dead-end of v1

Our first version made you happy and we love that.

But architecturally, it was a dead-end.

Maintaining it was a bear: documentation for the LLM was embedded in its code. Because of how fast both software frameworks and PostHog itself evolves, the documentation was constantly falling out of sync with our website, not the mention the web frameworks it targeted.

This was a great MVP, but it emerged before we were all savvy to context engineering

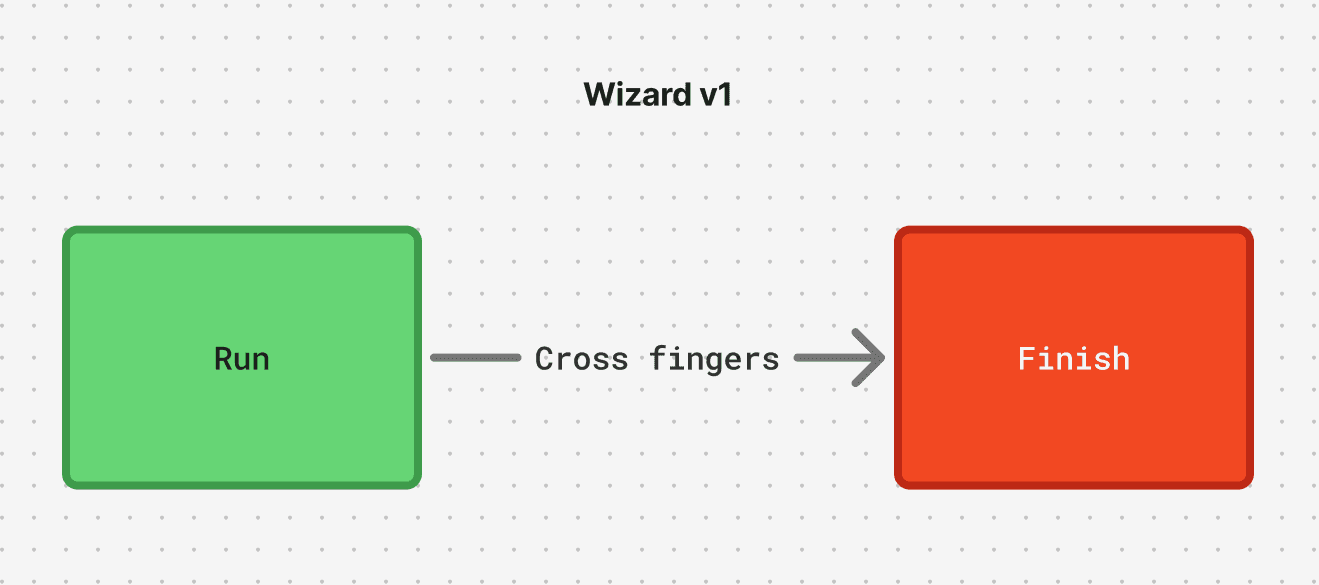

Worse still, the Wizard relied on a sort of Pareto luck: 80% of the time it could make the right edits. The rest of the time, it completely failed. It was a single-shot edit driven by an LLM, but scaffolded by a bunch of conventional code that hoped to find the right files. If your project was just a little weird, even just part of a monorepo, you were out of luck.

Most damning, the Wizard didn’t know if it succeeded. It crossed its fingers.

All of this presented a low ceiling. We could install code snippets, but we couldn’t be more ambitious for you. We needed better tools.

Agents change the game

Norbert Wiener, father of cybernetics, writes:

the structure of the machine or organism is an index of the performance that may be expected from it.

This observation, echoing 75 years from the past, rang true: we had a CLI that was built to explore a specific set of paths that might contain relevant files. It could read them and write them. But this was a straitjacket. We couldn’t possibly code ahead of all the permutations that it might encounter.

Its performance was capped by its structure.

So we needed new structure.

Instead of a car on a rail, we needed something that could steer, even backtrack, steadily circling in on its goal.

A tool like the Claude Agent SDK is perfect for this: it’s structured to both explore and integrate feedback. If a file isn’t where an agent expects, it can run a bash command to go looking for it.

By contrast to our crude CLI, the agent was nimble as a spider. It could detect coding errors, and it could trigger linters, type checkers, and prettiers. It could come at a problem from multiple angles.

The agent had all of the information encoded in the language model to inform its moves, and a broad set of tools it could use to make those moves.

Agents need less luck. But they do need loads of context.

Bringing the light of context

I’d get emails over the summer: the wizard had correctly integrated PostHog, but it was using a newer approach than we’d documented on the website.

This, understandably, made folks uneasy. Did the robot hallucinate this pattern?

The future of the Wizard needed to be hand-in-glove with whatever we’d written on posthog.com. Both sources had to agree.

Today, the Wizard is always primed with up-to-the-second documentation from the website. If a framework gets a new way of integrating analytics, all we need is a website update for both humans and the wizard to do better. This saves a ton of labor, and it lets us trim back the wizard to something lighter. No more docs embedded in the code.

But prose documentation alone, it turned out, was not enough. We needed a little more detail to ensure correctness. So for every framework we support, we build a toy project in code. These are not starter projects and you should not ship them: most obviously, the authorization flows are completely fake. They accept any password. Still, they demonstrate a PostHog integration in motion, giving the agent richer influence for doing the right thing.

Progressive disclosure

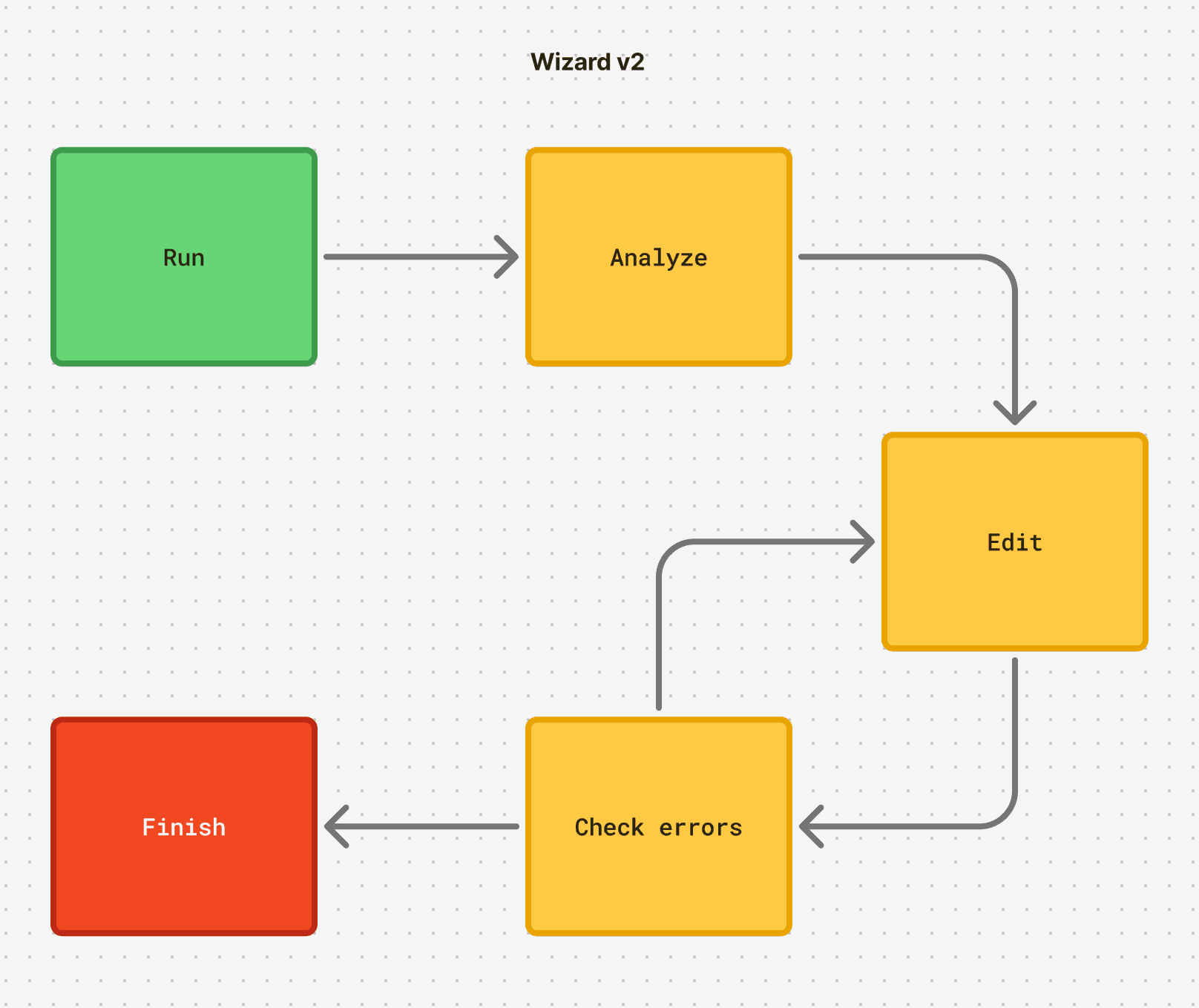

The last wrinkle for a robot making thousands of project edits per month was harder: how do you do the work predictably?

LLMs are non-deterministic systems. That’s the devil’s agreement of working with them. An agent can come up with many patterns and sequences for accomplishing the same goal.

What worked best for us was bread-crumbing the prompts, revealing them in sequence. Instead of dumping the entire plan right away, we disclose bits at a time.

You can do this without any fancy agent orchestration code. This is one of the strangest adjustments to make in the age of LLMs: you can accomplish so much with just natural language.

MCP ties this all together in a way that creates amazing outcomes from our agent, while allowing all the content investments we’re making to be reusable elsewhere – say, your Cursor or Claude Code session.

Everyone thinks about tools in MCP servers, but they can do other things too, like deliver resources. Resources bind data to a deterministic, consistent URI. You can be assured that posthog://my-great-prompt will always lead to the content you want.

This allows the dog to take itself for a walk. For each stage of an integration, the agent is prompted with a set of tasks. Once those tasks are complete, the agent is told to load the next piece of of the prompt.

Here’s an example, from the second-to-last stage of integration:

The result is that every integration follows the same general path and procedure, one that we know delivers great results.

I have to underscore that this piece created the breakthrough. The early agent-driven runs were useless in how variable they were. Sometimes integrations were solid. More often they were terrible. But the variability was the worst part. We couldn't ship something to users that was so unpredictable.

Staging the context created something predictable and trustworthy.

MCP is your friend

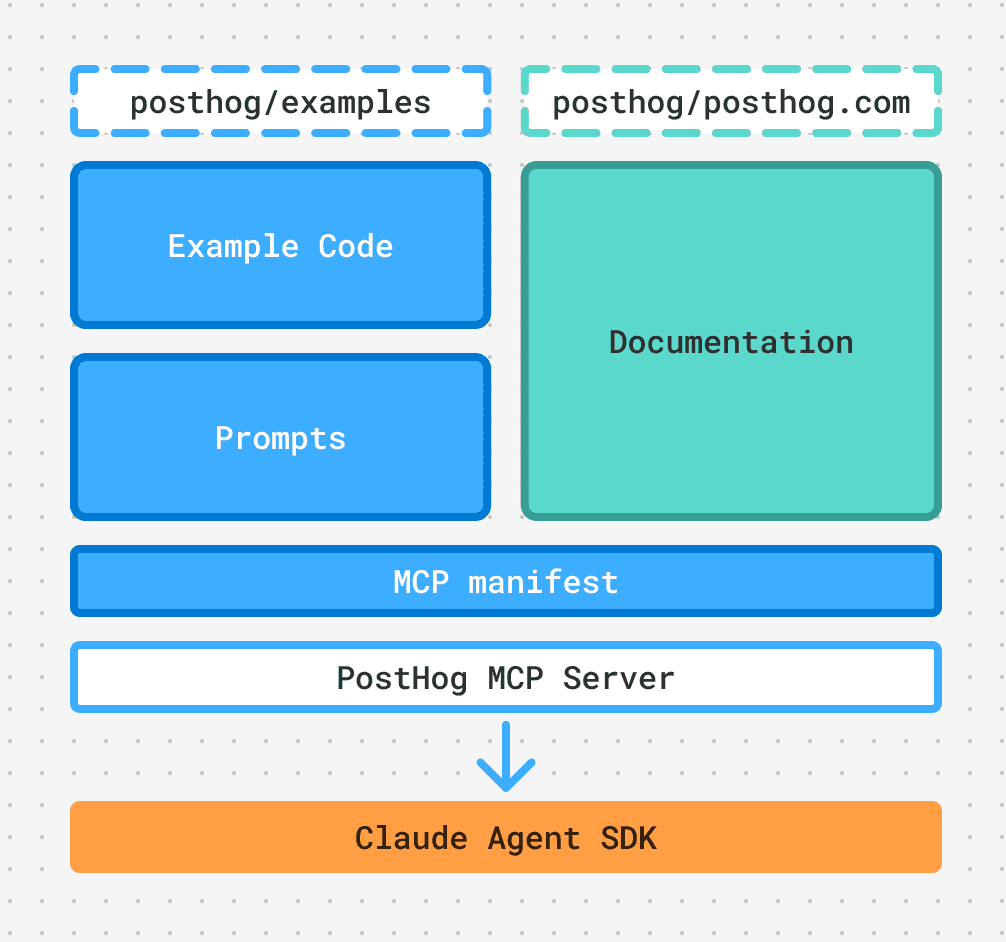

Best of all, where this content comes from is completely up to you in the design of an MCP server. It's a server you can design any way you want. We combine PostHog website content with sample code and prompts from a GitHub repo. The MCP can synthesize as many sources as you need into a single, one-stop surface for an agent to learn what it needs.

Other projects use MCP to deliver universal static analysis to course correct wayward agents, and even report errors to them live.

This is the most crucial job for successful LLM code generation: models are expensive to train, so the information they encode rots. In the case of PostHog integration code, it rots fast, as PostHog and the larger ecosystem are both constantly shipping. Patching the rot with fresh context changes everything.

MCP provides a universal surface to meet this goal. No lock-in. You can change agents, you can use multiple kinds of agents.

What comes next?

The hard bit was a reliable delivery vehicle.

We had some false starts. I shipped a beta of the new Wizard that didn’t actually bundle the Claude Agent CLI binary.

But I didn’t notice because I had Claude Code installed locally, and the Wizard just used that.

And then, it still worked in production for many people, because they also had Claude Code installed.

It’s weird out here.

Now the problem is designing just enough context that the Wizard can serve way more languages and frameworks. So while we crack away at that, steal what’s interesting:

- Because MCPs can do anything, you can use them for great user experiences. We just shipped the ability for the Wizard to create product analytics insights and dashboards. Think about how your own MCP can act as a butler.

- The AI Wizard repo is in a state of transition. Next.js is complete. You can compare our new approach to the old one by looking at the diff in this pull request. Look how much we get to delete!

- Our examples repo is full of example code and the prompts we’re using

- The PostHog MCP server uses the examples repo to construct its resource offerings

- This project owes a debt to Letta, whose context engineering and agent tools were essential for prototyping and developing my intuition around agent behavior. Try them out!

Now go forth and make the robots do your bidding!

PostHog is an all-in-one developer platform for building successful products. We provide product analytics, web analytics, session replay, error tracking, feature flags, experiments, surveys, LLM analytics, data warehouse, CDP, and an AI product assistant to help debug your code, ship features faster, and keep all your usage and customer data in one stack.