From $0 to $40M ARR - Inside the tech that powers Bolt.new

Contents

If you've started a new side-project recently, there's a good chance you've bumped into Bolt – a one-prompt app builder that went viral thanks to demos that look like magic. Type a sentence, wait a few seconds, and out pops a fully running project.

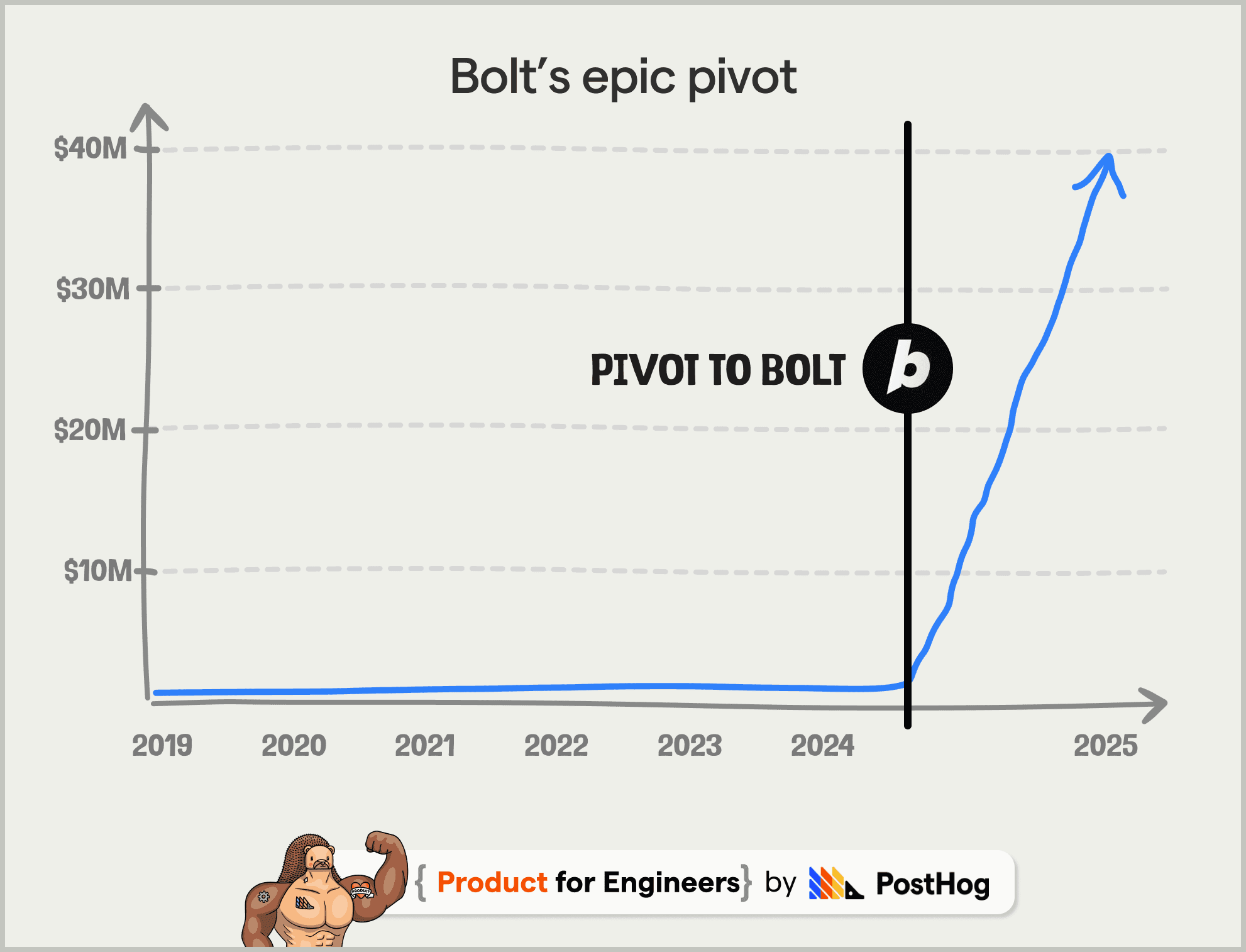

From the outside, Bolt seems like an overnight success story – another startup riding the wave of the AI boom. In fact, Bolt is among the most successful startup pivots ever. An overnight success that was seven years in the making.

This graph speaks for itself. Since that pivot in October 2024, Bolt’s users have created millions of apps, and Bolt is generating $40 million in ARR with an engineering team of just 15. A truly epic turnaround.

I spoke with co-founder and CTO Albert Pai, and founding engineer Dominic Elm, to understand how Bolt puts the rabbit into the hat.

How Bolt works

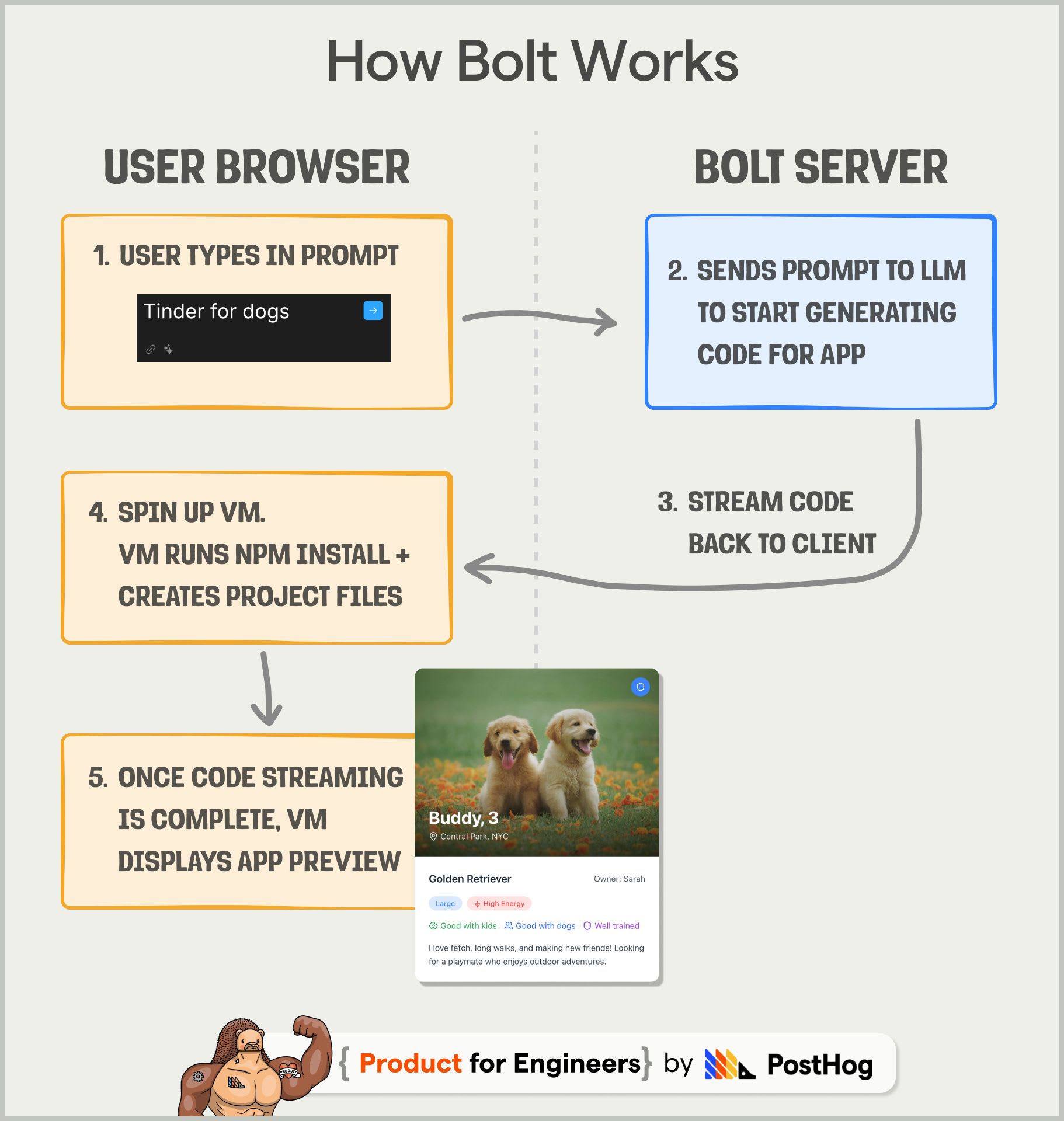

To understand some of the technical challenges of building Bolt, let's see what happens after entering a prompt:

- User types in a prompt, e.g. “Build a Tinder for Dogs web app.”

- Prompt is sent to an LLM to generate the code for the app.

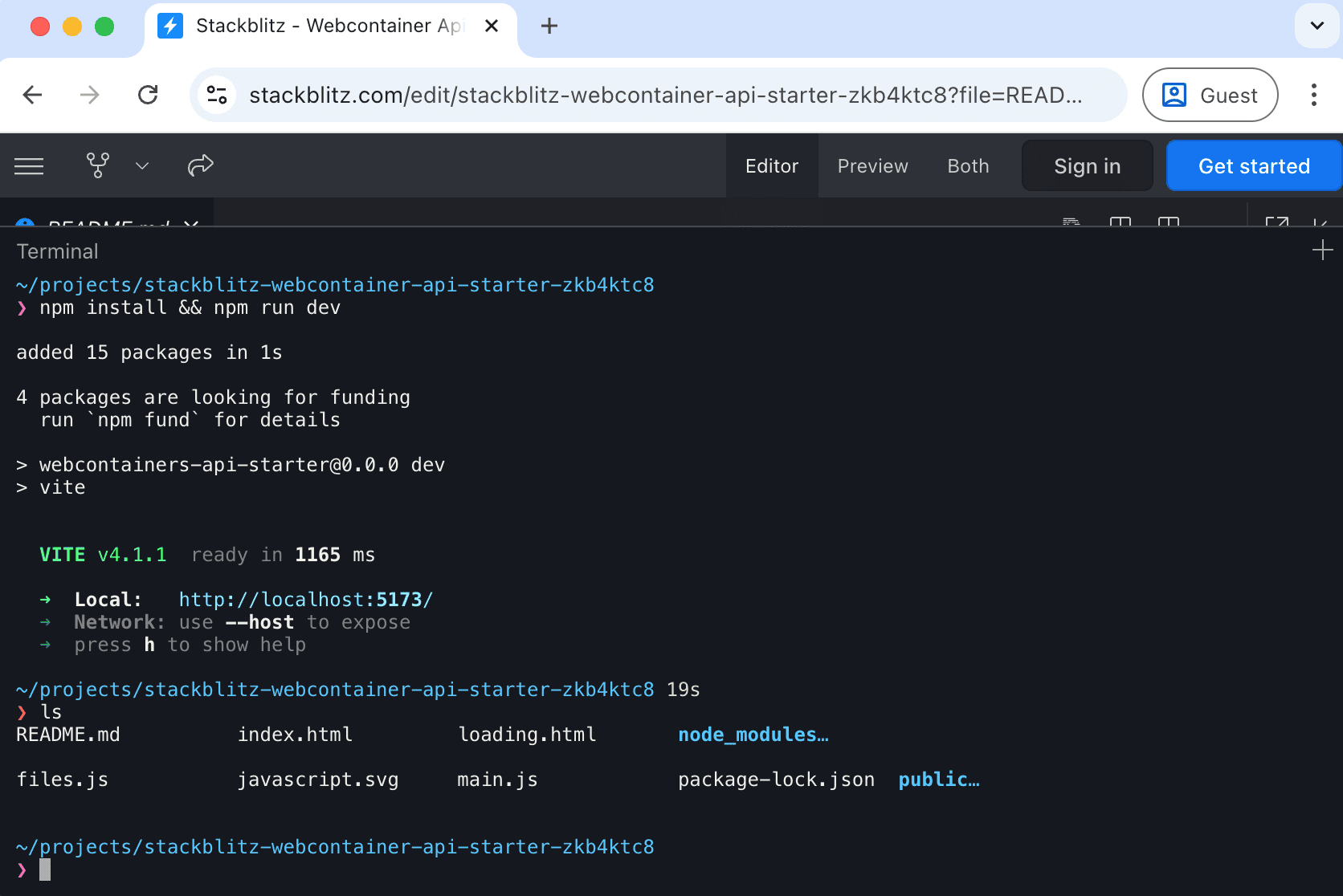

- In the meantime, the browser boots up WebContainer, an in-browser virtual machine where all the code will run.

- WebContainer receives the necessary commands to set up and install the project – e.g. it runs

npm install, creates project files, etc. - Once code is completed, the VM runs the code and displays the preview.

What's fascinating to me is how simple it all is.

I thought Bolt would be orchestrating a whole chain of LLM calls and fine-tuned models, but in reality the entire app springs from a single, meticulously crafted prompt.

The real story here is WebContainer, Bolt's in-browser VM. As Albert Pai, Bolt’s founder and CTO, notes: “People assume we’re running a giant server farm. In reality, the server is your browser.”

Before pivoting to building Bolt, the team spent seven years building StackBlitz, a browser-based IDE. StackBlitz's core tech was WebContainer, an open-source runtime they built that boots up Node.js entirely in a browser.

Despite millions of developer sessions, StackBlitz was on the brink of shutting down. Then, in mid-2024, the latest wave of LLMs proved that AI could build high quality apps end-to-end.

Recognizing that WebContainer was the perfect runtime for this new workflow, they pivoted and relaunched as Bolt in October 2024. In only 30 days they rocketed from $0 to $4M ARR, and six months later they 10×'ed to $40M.

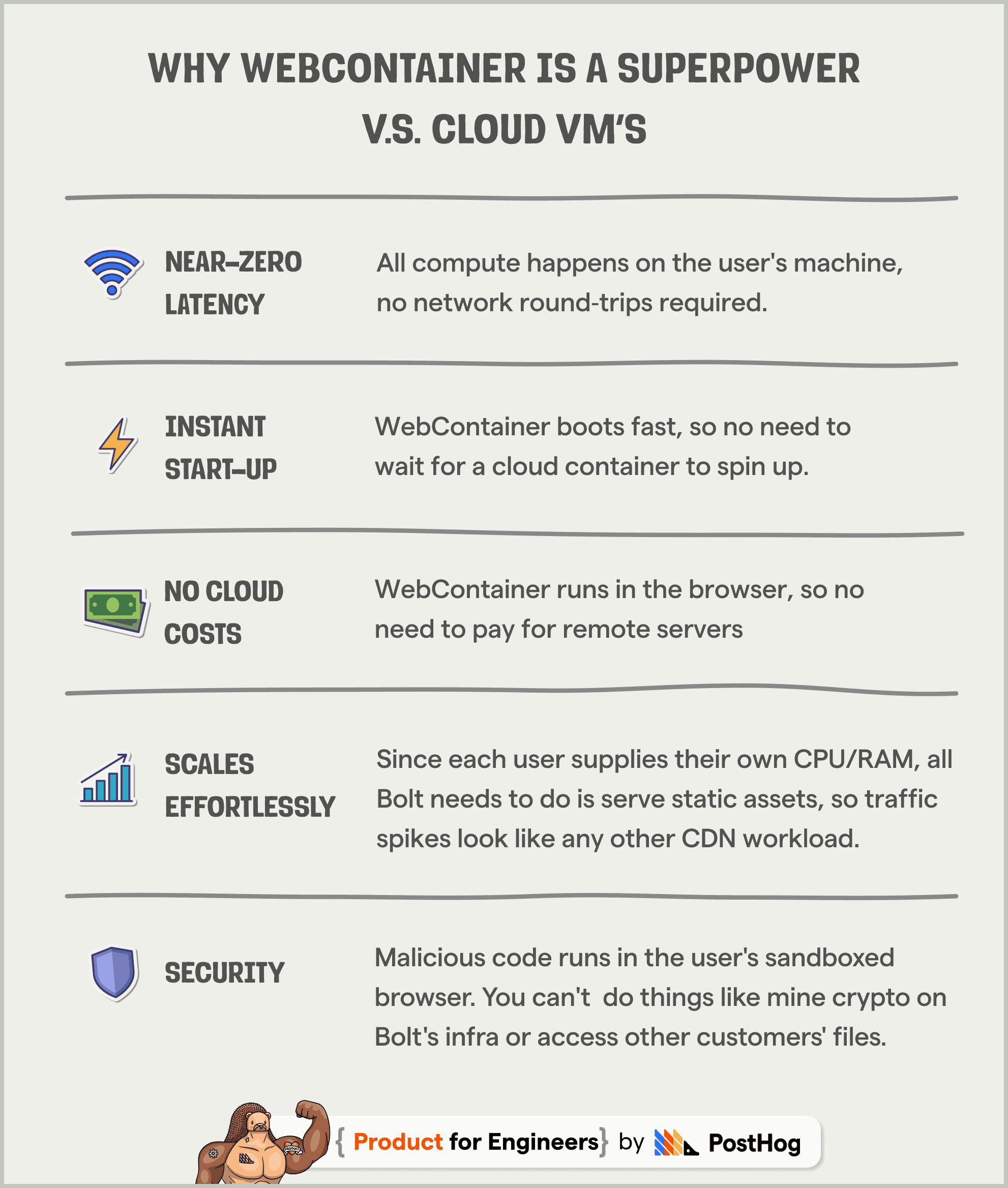

WebContainer is Bolt’s superpower. Most AI app builders spin up a fresh container in the cloud for every session, which adds cold starts, network round-trips, and per-user costs. WebContainer flips that model: it runs the app inside your browser.

“The big win is latency. It feels as if you’re developing on localhost,” says founding engineer Dominic Elm. “Plus it has security benefits. With remote compute you get abuse like people trying to run bitcoin miners. With WebContainer, if someone tries, they’re just using their own CPU.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Read by 100,000+ founders and builders

We'll share your email with Substack

Why squeezing Node.js into a browser tab is hard – and how Bolt pulled it off

Building this superpower wasn’t as easy as being bitten by a radioactive spider.

“At the beginning, we weren’t even sure it was possible. Browsers don’t expose the syscalls Node expects and have strict security rules,” says Albert. “We ended up spending years porting and building our own pieces until it actually felt like a local dev environment.”

Below, each major hurdle becomes its own mini-story.

1. A virtual file system

Node’s fs API expects a concurrent POSIX-compliant disk. Without it, even a simple npm install falls apart.

🛑 Why this is hard to do in a browser

Browsers don't expose the low-level file system operations that Node relies on – e.g. opening a file, locking it, writing raw bytes, etc. You have to simulate a real disk and safe concurrent access on top of higher-level browser primitives, which increases latency and the risk of race conditions.

It took three full attempts before the team had a browser-native file system fast enough.

First, they tried to fork an existing browser file system library. This failed quickly as most libraries only emulate the basics of a disk. Node expects dozens of low-level operations (file-descriptor locks, atomic writes, access controls), so the missing functions caused many errors.

Next they tried to write their own JavaScript-based file system. This approach relied on keeping every file in memory, and using a single dedicated Web Worker to handle all reads and writes via postMessage. However, with thousands of tiny files in something like a React app, requests pile up behind the worker, causing performance to tank and the UI to freeze.

💪 How Bolt pulled it off

Bolt built a Rust-based file system. Rust runs near C-speed, has zero GC pauses, and strong memory-safety – exactly what you want for something acting like an OS kernel. Combined with the Atomics API they built the atomic writes and file locks Node expects.

Whenever a Bolt tab opens, the file system module is loaded into a single SharedArrayBuffer – a block of memory that all Web Workers can access at the same time. Each Worker gets a reference to this buffer and treats it as the “disk”. Because they read/write directly in shared memory, there's no JSON copying and no slow async storage calls, making it far faster than the postMessage approach or alternatives like IndexedDB or OPFS.

Finally, at build-time the Rust code compiles to WebAssembly (WASM), so any modern browser can run it at near-native speed. The result is a crash-resistant, high-speed file system that meets Node's expectations.

2. A true process and threading model

Modern Node apps don't run in a single thread. When you type npm run dev, Node may:

- Spawn the TypeScript compiler in one process

- Launch Vite's web server in another

- Keep the Jest test-runner idling in the background

- Spin up worker threads for CPU-heavy tasks

🛑 Why this is a problem in a browser

Inside the browser you only get one UI thread and a handful of Web Workers. Workers can't fork() new processes, share open files/sockets, or handle OS-level signals. Node's tool-chain expects full operating-system processes with all those capabilities.

💪 How Bolt pulled it off

a. Web Workers as processes.

Every Node "process" becomes its own Worker. A tiny Rust “kernel” keeps a list of running tasks and exposes functions, so commands like ps or kill still work as expected.

b. One shared memory space.

All Workers share a single SharedArrayBuffer, so they read/write bytes directly. Atomics provide locks and atomic writes for safe concurrent FS access and fast inter-process communication.

c. Signal & stdio emulation.

The kernel sets tiny in-memory flags to request a task stop; Workers check those flags and shut down cleanly. For output, each Worker writes logs into its own shared log buffer, which the terminal reads directly.

d. Custom shell.

Since you can't embed a full Bash binary in a tab, Bolt shipped its own TypeScript shell called JSH. It understands everyday commands (cd, ls, npm run dev), keeps arrow-key history, and everything else you would expect. Behind the scenes every command runs in a Web Worker, but JSH funnels their input and output into one terminal pane, giving you a familiar “local” shell experience entirely inside the browser.

3. Networking without localhost

Dev servers usually bind to 127.0.0.1:PORT to run and test apps.

🛑 Why this is a problem in a browser

Code running inside a browser cannot listen on a port. The sandbox only lets pages initiate requests with fetch() or WebSockets. There's no raw TCP API, no listen(), and therefore no true localhost.

💪 How Bolt pulled it off

a. Virtual localhost via Service Worker.

A Service Worker watches for special in-page URLs (e.g. /__bolt/3000/...). When it sees one, it hands the request to the Web Worker that owns port 3000 via a fast MessagePort. To the dev server, it feels like a normal socket; to the page, it's just another fetch().

b. WebSocket bridge for hot-reload.

The same Service Worker intercepts WebSocket connections to that internal URL, opens a channel to the dev-server Worker, and forwards messages between them — keeping Vite/Next.js hot-reload working in tens of milliseconds.

c. Fallback tunnel for tools that expect raw TCP.

If some code tries to open a raw TCP socket (e.g., a Postgres client), Bolt swaps in a WebSocket replacement. The browser connects a Bolt relay server, which opens the real TCP connection and relays bytes both ways. Code keeps working while the browser stays sandboxed.

4. Standards-compliant ES Modules (ESM)

Modern Node lets you mix ES Modules (import …) and legacy CommonJS (require(), __dirname, etc.). If Bolt didn't support both inside the tab, much of the npm ecosystem would fail.

🛑 Why this is a problem in a browser

- URL-based resolution. Browsers fetch modules by absolute/relative URLs, but Node resolves via

node_modules,package.jsonexports, file extensions, etc. - CommonJS is missing.

require(),module.exports, and some dynamicimport()tricks don't exist natively. - Node’s VM & loader APIs are C++ and tied to the host OS.

💪 How Bolt pulled it off

a. Node-style resolver in TypeScript.

A custom loader reproduces Node’s behavior: climbs directories, reads package.json, honors exports/imports, adds missing extensions, falls back to index.js.

b. ESM ↔ CommonJS bridge.

If a module calls require('./utils'), Bolt’s loader detects it, wraps the CommonJS code, and injects it into the same dependency graph, so ESM and CJS can import each other seamlessly.

c. Virtual Node internals.

The Rust/WASM kernel exposes a fake process object (env, argv, cwd) and a slim vm API, giving Babel, TypeScript, and friends the hooks they expect.

5. Boot-time and runtime performance

Bolt has to feel as quick as opening a folder locally, even though the browser must download a Node-sized runtime and thousands of other project files.

🛑 Why this is hard in a browser

- Big download. A Node-compatible runtime plus helpers can weigh tens of MB.

- Thousands of tiny files. Extracting them one-by-one would freeze the UI.

- Slow installs.

npm installis network-heavy and noisy on the file system. - Tight CPU and memory budgets. A long compile or GC pause can freeze the tab.

💪 How Bolt pulled it off

a. Slim runtime bundle.

Dead code, debug symbols, and bulky unicode tables are stripped from the Rust→WASM build, pushing the cold download to well under 10 MB.

b. Snapshot-first file system.

The entire node_modules tree and project source are packed into one compressed blob. First load streams it straight into shared memory. Subsequent visits copy from the HTTP cache, taking hundreds of ms instead of seconds.

c. Instant installs.

Popular packages live on Bolt's CDN in pre-compressed layers. After the first hit they sit in the browser cache, so npm install often finishes in < 500 ms, or is skipped entirely.

d. Work off the main thread.

Compiles and builds run in Web Workers that yield regularly, keeping the UI free and GC pauses invisible.

Great tech + staying alive = Profit $

WebContainer is clearly an impressive piece of technology, but what really mattered was that the team never gave up on it.

“For seven years we kept grinding even when the results looked thin, and we were disciplined enough not to run out of money,” says Albert.

“This persistence meant that when LLMs finally became good enough to generate entire apps, we were holding the exact missing piece.”

Suddenly WebContainer wasn’t just a clever runtime, it was also the perfect companion for AI. With it, a one-line prompt could turn into a running full-stack app.

Bolt pivoted their business into the moment and, with a single tweet, years of quiet work ignited into explosive growth.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Read by 100,000+ founders and builders

We'll share your email with Substack

PostHog is an all-in-one developer platform for building successful products. We provide product analytics, web analytics, session replay, error tracking, feature flags, experiments, surveys, LLM analytics, data warehouse, CDP, and an AI product assistant to help debug your code, ship features faster, and keep all your usage and customer data in one stack.