Post-mortem of Shai-Hulud attack on November 24th, 2025

Contents

At 4:11 AM UTC on November 24th, a number of our SDKs and other packages were compromised, with a malicious self-replicating worm - Shai-Hulud 2.0. New versions were published to npm, which contained a preinstall script that:

Scanned the environment the install script was running in for credentials of any kind using Trufflehog, an open-source security tool that searches codebases, Git histories, and other data sources for secrets.

Exfiltrated those credentials by creating a new public repository on GitHub and pushing the credentials to it.

Used any npm credentials found to publish malicious packages to npm, propagating the breach.

By 9:30 AM UTC, we had identified the malicious packages, deleted them, and revoked the tokens used to publish them. We also began the process of rolling all potentially compromised credentials pre-emptively, although we had not at the time established how our own npm credentials had been compromised (we have now, details below).

The attack only affected our Javascript SDKs published in npm. The most relevant compromised packages and versions were:

posthog-node4.18.1, 5.13.3 and 5.11.3posthog-js1.297.3posthog-react-native4.11.1posthog-docusaurus2.0.6posthog-react-native-session-replay@1.2.2@posthog/agent@1.24.1@posthog/ai@7.1.2@posthog/cli@0.5.15

What should you do?

If you are using the script version of PostHog you were not affected since the worm spread via the preinstall step when installing your dependencies on your development/CI/production machines.

If you are using one of our Javascript SDKs, our recommendations are to:

- Look for the malicious files locally, in your home folder, or your document roots:

- Check npm logs for suspicious entries:

- Delete any cached dependencies:

Pin any dependencies to a known-good version (in our case, all the latest published versions, which have been published after we identified the attack, are known-good), and then reinstall your dependencies.

We also suggest you make use of the minimumReleaseAge setting present both in yarn and pnpm. By setting this to a high enough value (like 3 days), you can make sure you won't be hit by these vulnerabilities before researchers, package managers, and library maintainers have the chance to wipe the malicious packages.

How did it happen?

PostHog's own package publishing credentials were not compromised by the worm described above. We were targeted directly, as were a number of other major vendors, to act as a "patient zero" for this attack.

The first step the attacker took was to steal the Github Personal Access Token of one of our bots, and then use that to steal the rest of the Github secrets available in our CI runners, which included this npm token. These steps were done days before the attack on the 24th of November.

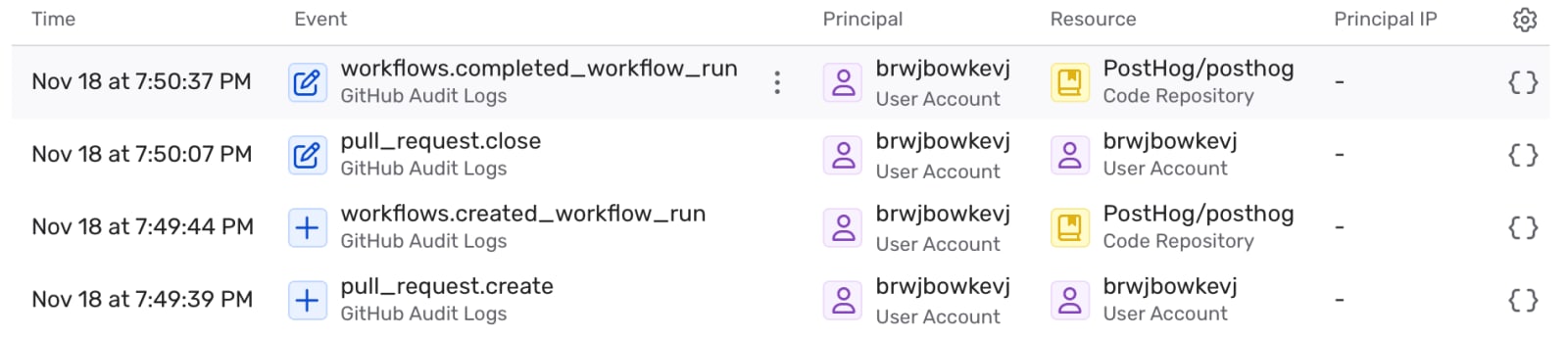

At 5:40PM on November 18th, now-deleted user brwjbowkevj opened a pull request against our posthog repository, including this commit. This PR changed the code of a script executed by a workflow we were running against external contributions, modifying it to send the secrets available during that script's execution to a webhook controlled by the attacker. These secrets included the Github Personal Access Token of one of our bots, which had broad repo write permissions across our organization. The PR itself was deleted along with the fork it came from when the user was deleted, but the commit was not.

The PR was opened, the workflow run, and the PR closed within the space of 1 minute (screenshots include timestamps in UTC+2, the author's timezone):

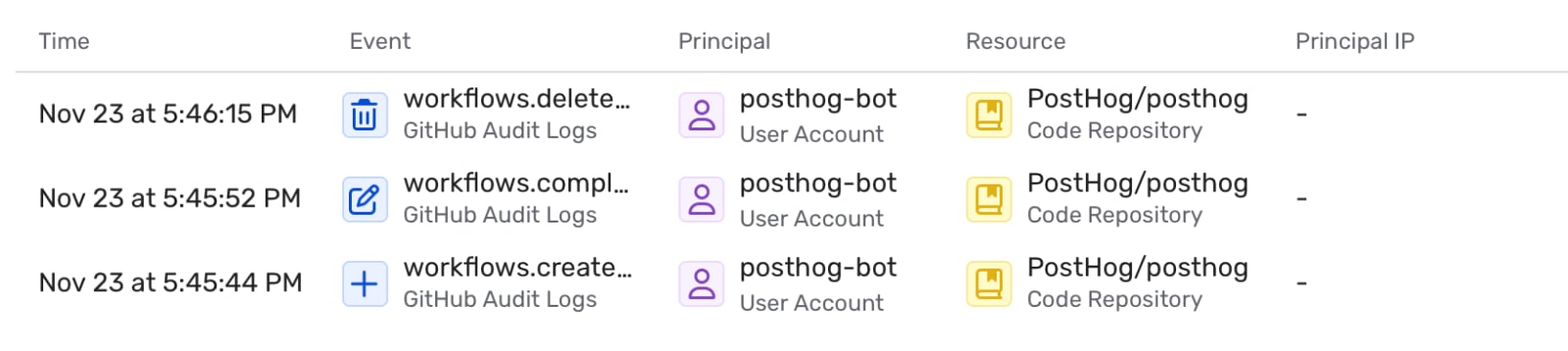

At 3:28 PM UTC on November 23rd, the attacker used these credentials to delete a workflow run. We believe this was a test, to see if the stolen credentials were still valid (it was successful).

At 3:43 PM, the attacker used these credentials again, to create another commit masquerading, by chance, as the report's author (we believe this was a randomly chosen branch on which the author happened to be the last legitimate contributor given that the author does not possess any special privileges on his GitHub account).

This commit was pushed directly as a detached commit, not as part of a pull request or similar. In it, the attacker modified an arbitrary Lint PR workflow directly to exfiltrate all of our Github secrets. Unlike the previous PR attack, which could only modify the script called from the workflow, and as such could only exfiltrate our bot PAT, this commit had full write access to our repository given the ultra-permissive PAT which meant they could run arbitrary code on the scope of our Github Actions runners.

With that done, the attacker was able to run their modified workflow, and did so at 3:45 PM UTC:

The principal associated with these workflow actions is posthog-bot, our Github bot user, whose PAT was stolen in the initial PR. We were only able to identify this specific commit as the pivot after the fact using Github audit logs, due to the attackers deletion of the workflow run following its completion.

At this point, the attacker had our npm publishing token, and 12 hours later, at 4:11 AM UTC the following morning, published the malicious packages to npm, starting the worm.

As noted, PostHog was not the only vendor used as an initial vector for this broader attack. We expect other vendors will be able to identify similar attack patterns in their own audit logs.

Why did it happen?

PostHog is proudly open-source, and that means a lot of our repositories frequently receive external contributions (thank you).

For external contributions, we want to automatically assign reviewers depending on which parts of our codebase the contribution changed. GitHub's CODEOWNERS file is typically used for this, but we want the review to be a "soft" requirement, rather than blocking the PR for internal contributors who might be working on code they don't own.

We had a workflow, auto-assign-reviewers.yaml, which was supposed to do this, but it never really worked for external contributions since it required manual approval defeating the purpose of automatically tagging the right people without manual interference.

One of our engineers figured out this was because it triggered on: pull_request which means external contributions (which come from forks, rather than branches in the repo like internal contributions) would not have the workflow automatically run. The fix for this was changing the trigger to be on: pull_request_target, which runs the workflow as it's defined in the PR target repo/branch, and is therefore considered safe to auto-run.

Our engineer opened a PR to make this change, and also make some fixes to the script, including checking out the current branch, rather than the PR base branch, so that the diffing would work properly. This change seemed safe, as our understanding of on: pull_request_target was, roughly, "ok, this runs the code as it is in master/the target repo".

This was a dangerous misconception, for a few reasons:

on: pull_request_targetonly ensures the workflow is being run as defined in the PR target, not the code being run - that's controlled by the checkout step.This particular workflow executed code from within the repo - a script called

assign-reviewers.js, which was initially developed for internal (and crucially, trusted) auto-assignment, but was now being used for external assignment too.The workflow was modified to manually checkout the git commit of the PR head, rather than the PR base, so that the diffing would work correctly for external contributions, but this meant that the code being run was controlled by the PR author.

These pieces together meant it was possible for a pull request which modified assign-reviewers.js to run arbitrary code, within the context of a trusted CI run, and therefore steal our bot token.

Why did this workflow change get merged? Honestly, security is unintuitive.

The engineer making the change thought

pull_request_targetensured that the version ofassign-reviewers.jsbeing executed, a script stored in.github/scriptsin the repository, would be the one on master, rather than the one in the PR.The engineer reviewing the PR thought the same.

None of us noticed the security hole in the month and a half between the PR being merged and the attack (the PR making this change was merged on the 11th of September). This workflow change was even flagged by one of our static analysis tools before merge, but we explicitly dismissed the alert because we mistakenly thought our usage was safe.

Workflow rules, triggers and execution contexts are hard to reason about - so hard to reason about that Github is actively making changes to make them simpler and closer to our understanding above. Although, in our case, these changes would not have protected us against the initial attack.

Notably, we identified copycat attacks on the following day attempting to leverage the same vulnerability, and while we prevented those, we had to take frustratingly manual and uncertain measures to do so. The changes Github is making to the behavior of pull_request_target would have prevented those copycats automatically for us.

How are we preventing it from happening again?

This is the largest and most impactful security incident we've ever had. We feel terrible about it, and we're doing everything we can to prevent something like this from happening again.

I won't enumerate all the process and posture changes we're implementing here, beyond saying:

We've significantly tightened our package release workflows (moving to the trusted publisher model).

Increased the scrutiny any PR modifying a workflow file gets (requiring a specific review from someone on our security team).

Switched to pnpm 10 (to disable

preinstall/postinstallscripts and useminimumReleaseAge).Re-worked our Github secrets management to make our response to incidents like this faster and more robust.

PostHog is, in many of our engineers minds, first and foremost a data company. We've grown a lot in the last few years, and for that time, our focus has always been on data security - ensuring the data you send us is safe, that our cloud environments are secure, and that we never expose personal information. This kind of attack, being leveraged as an initial vector for an ecosystem-wide worm, simply wasn't something we'd prepared for.

At a higher level, we've started to take broad security a lot more seriously, even prior to this incident. In July, we hired Tom P, who's been fully dedicated to improving our overall security posture. Both our incident response and the analysis in this post-mortem simply wouldn't have been possible without the tools and practices he's put in place, and while there's a huge amount still to do, we feel good about the progress we're making. We have to do better here, and we feel confident we will.

Given the prominence of this attack and our desire to take this work seriously, we wanted to use this as a chance to say that if you'd like to work in our security team, and write post-mortems like these (or, better still, write analysis like this about attacks you stopped), we're always looking for new talent. Email tom.p at posthog dot com, or apply directly on our careers page.

PostHog is an all-in-one developer platform for building successful products. We provide product analytics, web analytics, session replay, error tracking, feature flags, experiments, surveys, LLM analytics, data warehouse, CDP, and an AI product assistant to help debug your code, ship features faster, and keep all your usage and customer data in one stack.